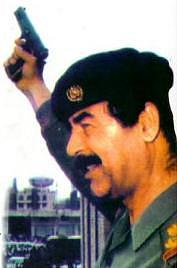

The Anfal campaign, where the Iraqi government under President Saddam Hussein attacked Kurds living in Iraq, took place between late February and early September in 1988. The campaign had both genocidal and gendercidal aspects and aimed to not only eliminate Kurdish insurgents but also Arabize strategic parts of northern Iraq.

The Anfal campaign was a part of a longer campaign that resulted in the destruction of an estimated 4,500 Kurdish villages and over 30 Assyrian Christian villages in northern Iraq. It also displaced at least one million of the estimated 3.5 million Kurds living in Iraq at the time.

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), the primary targets of the Anfal campaign was Kurdish men of battle-age. “Throughout Iraqi Kurdistan, although women and children vanished in certain clearly defined areas, adult males who were captured disappeared en masse. (…) It is apparent that a principal purpose of Anfal was to exterminate all adult males of military service age captured in rural Iraqi Kurdistan.” (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 96, 170)

Headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid, a cousin of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, the Anfal campaign utilized the Iraqi military and also had support from Kurdish collaborators; the so-called Jash forces. The Jash helped the army locate Kurdish settlements not marked on official maps, and also led them to secret Kurdish hiding spots in the mountains. The Jash was also used to lure out Kurds through the use of false promises of safe passage or amnesty.

Headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid, a cousin of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, the Anfal campaign utilized the Iraqi military and also had support from Kurdish collaborators; the so-called Jash forces. The Jash helped the army locate Kurdish settlements not marked on official maps, and also led them to secret Kurdish hiding spots in the mountains. The Jash was also used to lure out Kurds through the use of false promises of safe passage or amnesty.

The attacks on Kurds included ground offensives, mass deportations, systematic destruction of settlements, firing squads, chemical warfare, and aerial bombings. “By the time the genocidal frenzy ended, 90% of Kurdish villages, and over twenty small towns and cities, had been wiped off the map. The countryside was riddled with 15 million landmines, intended to make agriculture and husbandry impossible. A million and a half Kurdish peasants had been interned in camps.” (Source: Kendal Nezan, “When our ‘friend’ Saddam was gassing the Kurds”, Le Monde diplomatique, March 1998.)

During the Anfal campaign, the United States under President Ronald Reagan continued to give military aid to Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, even after being aware of the use of toxic gas against Kurdish civilians. (Source: Shane Harris, “Exclusive: CIA Files Prove America Helped Saddam as He Gassed Iran”, Foreign Policy, 2013. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/08/26/exclusive-cia-files-prove-america-helped-saddam-as-he-gassed-iran)

Before the Anfal campaign was over, at least 50,000 rural Kurds had died, but finding an exact number has proven difficult. Some sources claim significantly higher numbers, such as 100,000 or more, based on other estimates, findings and witness reports.

Journalist Jonathan C. Randal writes about a death toll of 60,000 to 110,000 for a time period running from shortly befall the first stage of the Anfal and ending shortly after the last stage of the campaign. “On the basis of extensive interviews in Kurdistan and perusal of extant Iraqi documents, Shoresh Resoul, a meticulous Kurdish researcher (…) conservatively estimated that ‘between 60,000 and 110,000’ died during Majid’s Kurdish mandate.” (Source: Jonathan C. Randal, “After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness? My Encounters With Kurdistan”, 1998, p. 230.)

Kenneth Roth, director of Human Rights Watch, has referred to the “100,000 Kurdish men and boys machine-gunned to death during the 1988 Anfal genocide“, which indicates that the Anfal deaths of other members of the Kurdish community is to be put on top of the 100k to reach an accurate total death toll. (Source: Kenneth Roth, “Show Trials Are Not the Solution to Saddam’s Heinous Reign”, The Globe and Mail, 18 July 2003.)

General sources and recommended further reading:

- Amnesty International, “Iraq: ‘Disappearances’ – the agony continues” https://web.amnesty.org/pages/irq-article_6-eng

- Certrez, Donabed, and Makko (2012). The Assyrian Heritage: Threads of Continuity and Influence. Uppsala University. p. 288.

- BBC News, “Killing of Iraq Kurds ´genocide´, 23 December, 2005 https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4555000.stm

- Human Rights Watch Report, “Whatever Happened to the Iraqi Kurds?”, 1991https://www.hrw.org/reports/1991/IRAQ913.htm

The Anfal campaign

In March 1987 Saddam Hussein´s cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, already well known for his brutality, was appointed secretary-general of Ba´ath Party´s northern division, a move that placed al-Majid in charge of the region that included Iraqi Kurdistan. Under his time in power, control of the anti-insurgent work in the region passed from the army to the Ba´ath Party.

In March 1987 Saddam Hussein´s cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, already well known for his brutality, was appointed secretary-general of Ba´ath Party´s northern division, a move that placed al-Majid in charge of the region that included Iraqi Kurdistan. Under his time in power, control of the anti-insurgent work in the region passed from the army to the Ba´ath Party.

Within months of al-Majid´s appointment, the “final solution to the Kurdish problem” was set in motion. It was to be known as al-Anfal, which means “the spoils” and is a reference to a section in the Qur´an.

The Anfal campaign had a total of eight stages, and seven of them targeted areas controlled by PUK. While the campaign had access to approximately 200,000 soldiers from the Iraqi army, the Kurdish guerilla forces were comprised of just a few thousand people.

Gender-aspects of the Anfal campaign

In June 1987, directive SF/4008 was issued under al-Majid´s signature, and Clause 5 of the directive designated certain prohibited zones. As the directive came into force, al-Majid ordered that all persons captured in villages within the prohibited zones would be detained and interrogated by security services, and those between the ages 15-70 should be executed after interrogation.

Even though the order did not explicitly say so, males – not women – seems to have been the intended targets for execution.

As Human Rights Watch write in their report. “Under the terms of al-Majid’s June 1987 directives, death was the automatic penalty for any male of an age to bear arms who was found in an Anfal area.” (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 14)

In September 1987, a new directive was issued, calling for “the deportation of (…) families to the areas where there saboteur relatives are (…), except for the male [members], between the ages of 12 inclusive and 50 inclusive, who must be detained.” (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, p. 298)

When captured Kurds were transported to detention centres, boys and males deemed to have “battle ability” were separated from the rest of the groups – a pattern we recognize from many other genocidal and gendercidal campaigns throughout history.

Human Rights Watch has written a few passages about the standard pattern for sorting new arrivals at the Topzawa concentration camp near Kirkuk, roughly 150 miles north of Baghdad.

“Men and women were segregated on the spot as soon as the trucks had rolled to a halt in the base’s large central courtyard or parade ground. The process was brutal (…) A little later, the men were further divided by age, small children were kept with their mothers, and the elderly and infirm were shunted off to separate quarters. Men and teenage boys considered to be of an age to use a weapon were herded together. Roughly speaking, this meant males of between fifteen and fifty, but there was no rigorous check of identity documents, and strict chronological age seems to have been less of a criterion than size and appearance. A strapping twelve-year-old might fail to make the cut; an undersized sixteen-year-old might be told to remain with his female relatives. (…) It was then time to process the younger males. They were split into smaller groups. (…) Once duly registered, the prisoners were hustled into large rooms, or halls, each filled with the residents of a single area. (…) Although the conditions at Topzawa were appalling for everyone, the most grossly overcrowded quarter seem to have been those where the male detainees were held. (…) For the men, beatings were routine.” (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 143-145)

Human Rights Watch also reports how the adult and teenage men who had been removed from the rest of the population were executed within a few days after arriving to camp.

“Some groups of prisoners were lined up, shot from the front, and dragged into predug mass graves; others were made to lie down in pairs, sardine-style, next to mounds of fresh corpses, before being killed; still others were tied together, made to stand on the lip of the pit, and shot in the back so that they would fall forward into it — a method that was presumably more efficient from the point of view of the killers. Bulldozers then pushed earth or sand loosely over the heaps of corpses. Some of the grave sites contained dozens of separate pits and obviously contained the bodies of thousands of victims.” (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, p. 12)

Gender-aspects in regards to the different stages of the campaign

Males

As mentioned above, the Anfal campaign consisted of eight stages, and research has shown that the gender-dynamics of the Kurdish genocide varied depending on stage. There are for instance no reports of mass killings of civilians during the first stage, i.e. February 23 to March 19, 1988.

The most heavy targeting of males took place during the final stage, i.e. August 25 to September 6. This stage started right after Iraq´s ceasefire agreement with Iran, as military personnel and supplies could now be relocated from southern Iraq to the north. The final stage of the Anfal focused on roughly four-thousand-square miles of the Zagros Mountains. During this stage of the Anfal, many Kurdish males were not even sent to concentration camps first – they were simply executed locally at their point of capture. When the Human Rights Watch later researched the last stage of the Anfal, the survivors in the target region provided them with lists of people who had been disappeared during that stage. For the Kurds (except Yezidi Kurds), those lists only included adult and teenage males – indicating a very strict gender-selection. For Assyrians, Caldean Christians and Yezidi Kurds in the area, the gender-selection was less strict. (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 178, 190, 192, 209-213)

Females

While adult and teenage males were likely to be executed with a bullet, the other members of the Kurdish community who perished during the Anfal largely did so because of other reasons – such as starvation and exposure. They were also subjected to the now infamous gas attacks. According to Human Rights Watch, thousands of women, children and elderly Kurds died of the Anfal campaign.

(Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, p. 191)

While the treatment of battle-age Kurdish males was fairly uniform, large regional variations have been observed regarding the deaths of other members of the Kurdish community. Human Rights Watch has dubbed it one of the great enigmas of the Anfal campaign, as these deaths were subject to extreme regional variations, possibly caused by the presence of armed resistance. Most of the Kurds who died despite not being battle-age men belonged to one of two distinct clusters impacted by the third and fourth stage of the Anfal. One example of an area with many deaths was southern Germian, an area known for its strong support for PUK and for being located close to the Arab heartland in Iraq. This are was attacked at 7-20 April, 1988, during the third stage of the Anfal. (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 13, 96)

“Although males aged fifteen to fifty routinely vanished from all parts of Germian, only in the south did the disappeared include significant numbers of women and children. Most were from the Daoudi and Jaff-Roghyazi tribes.” In some areas, women and children accounted for half of the disappeared.

Human Rights Watch also reports how mass executions of women and children where held in southern Germian, including executions involving an estimated 2,000 women and children on Hamrin Mountain, between Tikrit and Kirkuk. (Source: Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 115, 171)

Mass executions of women and children locally soon after capture – such as those that took place in southern Germian – were not the norm during any stage of the Anfal. Instead, sending them (and Kurdish males not deemed suitable for battle) to camps in the south was the norm. In some cases, these people were later executed after having lived in the camps for a while. Also, the squalid conditions in these camps meant that thousands died without being outright executed, and children were especially at risk.

Understanding the context

The Kurdish people (the Kurds) are an ethnic group whose heartland is the mountainous region Kurdistan in Western Asia. Kurdistan is not a sovereign state; it is a region spanning south-eastern Turkey, north-western Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria.

As of 2020, the Kurdish population in and outside Kurdistan combined is comprised of an estimated 30-45 million people, including major Kurdish exclaves found in Central Anatolia, Khorasan, the Caucasus, Istanbul, and Germany.

After World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Western allies made provisions for a Kurdish sovereign state, as outlined in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres. After just three years, the promise to the Kurds was broken as the Western allies wished to appease the new Turkish regime of Kemal Ataturk. When the Treaty of Lausanne set the boundaries of modern Turkey in 1923, no provisions were made for a sovereign Kurdistan. The Western allies also refused to cede any land in Iraq or Syria to establish a sovereign Kurdistan, even though Iraq and Syria had been granted to Britain and France, respectively, as mandated territories.

The last hundred years have been marked by armed conflict in regards to Kurdistan, as Kurdish movements have fought against oppression and discrimination, and for greater cultural rights and autonomy from the sovereign states. In Iraq and Syria, regions with a higher degree of Kurdish autonomy now exist, but their situation is still precarious.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) was founded by Kurds in Iraq soon after the end of World War II, and it grew to be one of the most prominent of the Kurdish resistance organizations. The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) was established in 1975 as a more radical alternative to KDP, and PUK was the main target of the 1988 Anfal campaign.

Sources:

- Martin van Bruinessen, “Genocide in Kurdistan?,” in George J. Andreopoulos, ed., Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994, pp. 156-57

- Human Rights Watch, “Iraq’s Crime of Genocide: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds”, Yale University Press, 1995, pp. 4, 26-27)

Oil

During Saddam Hussein´s early years in power, things were beginning to look better for the Iraqi Kurds. In 1970 (when he was yet not president) his Ba´ath Party reached an agreement with Kurdish rebel groups and the Kurds earned certain rights and political autonomy.

This agreement eventually broke down due to an all-too-common reason: oil.

The Ba´ath Party launched an Arabization campaign for the oil-producing areas of Kurdistan. Kurds were banished and replaced with poor Arab tribespeople from southern Iraq that were expected to be loyal to the regime. In March 1974, the KDP rebelled, which resulted in a full-scale war. Some 130,000 Kurds fled to Iran in 1975, and in March that year tens and thousands of Kurds belonging to the Barzani tribes were expelled from their homes and moved to barren arid lands in the south.

A few years later, these expelled Barzani Kurds were subjected to a gendercidal massacre, which in many respects foreshadowed the much larger Anfal campaign against the Iraqi Kurds. The absence of international outcry over what happened to the Barzani seems to have strenghten the regime´s belief in being able to get away with a “final solution” in regards to the Kurds without outsiders intervening.

Source: Khaled Salih, “Anfal: The Kurdish Genocide in Iraq,” Digest of Middle East Studies 4: 2 Spring, 1995

International support of Saddam Hussein

During the war between Iran and Iraq in 1980-1988, Saddam Hussein was largely viewed by the West as a bulwark against the spread of Iranian-style Islamic fundamentalist regimes in the oil-rich countries of the Middle East. Therefore, Hussein received military supplies – including weapons – from Western countries, and was also provided with critical intelligence information.

Even as late as August 1988, when the Anfal campaign was in its later stages and the use of chemical weapons on civilians was well-known, the United Nations Sub-Committee on Human Rights voted by 11 to 8 to not condemn Iraq for human rights violations. Australia, Canada and the Scandinavian countries broke the norm by condemning Iraq, and so did certain international organizations and bodies, including the European Parliament and the Socialist International.

Saddam Hussein did not lose the support of his allies in the West until August 1990, when Iraq invaded its neighbour Kuwait.

Source: Kendal Nezan, “When our “friend” Saddam was gassing the Kurds”, Le Monde diplomatique, October 1988.